Peter Hagendorf, Mercenary Journal from the Thirty Years War (1625–1648)

Abstract

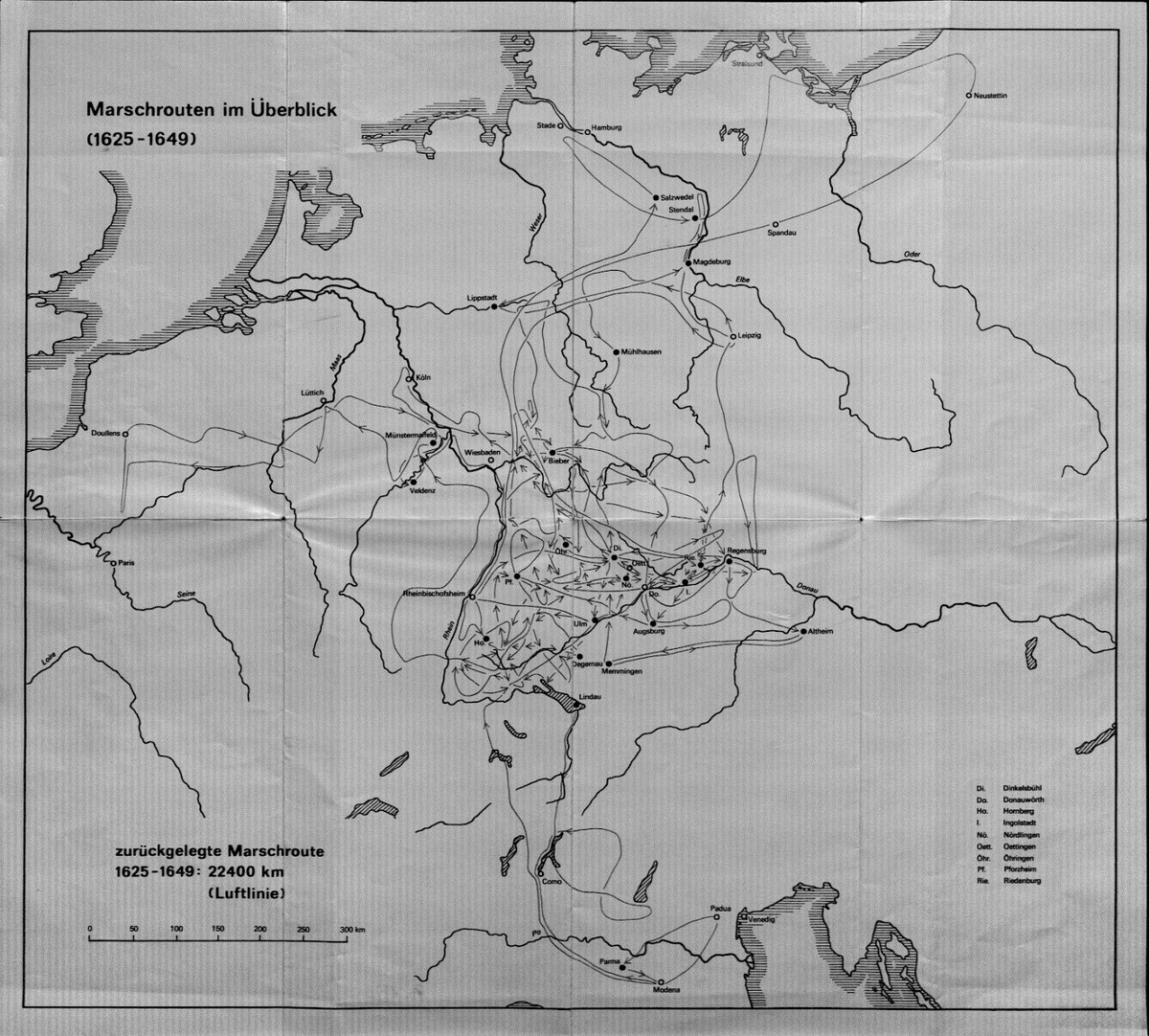

During the Thirty Years War soldier Peter Hagendorf marched through the German territories and through neighboring countries such as Italy (see the illustration of his route), recording his experiences in a kind of diary. Hagendorf presents himself as both a victim and perpetrator of wartime events. As a mercenary, he was involved in battles in various territories, and he describes the individual towns and landscapes that he traversed with an interest in regional character. The featured excerpt attests to the fact that fighting soldiers were often accompanied by their wives and children on the campaigns.

Source

2. The Text

[….] Here the Rhine runs through Lake Constance. From Lindau to Bregenz, to Maienfeld, over the steep mountain path to the Grisons [Graubünden], to Chur, the capital of the Grisons. They already speak welsch [one of the Romance languages]. It is all mountains and valleys.

The snow on the mountains does not go away for the entire summer. Cattle are raised here, but there is almost no grain farming, nor any vineyards, a very harsh land. Near Chur there is a nice hot spring, [which is] very curative.

From Chur to Splügen. The Rhine has its source here on this mountain. A whole day’s journey is required to reach the mountain’s top. In the middle of the mountain there is an inn. Near this inn it goes downhill again. This mountain is so high that a man can only walk single file, and the snow lies deep on the entire mountain.

Then to Chiavenna. Below the mountain everything is already welsch [Romance-language speaking]. There I bought myself a book, half welsch and half German, and sold my coat for three Thaler. Then to Riva along a mighty pass, with a pretty castle on the left side of the lake. Lake Como starts here. Mounted here and traveled to Lecco, a day’s journey; it belongs to the Venetians. This is the first city of this region, which belongs to the Venetians, Then to Bergamo, a beautiful city with a beautiful castle. Here Venetian land really starts. Then to Brescia, a beautiful city.

There I allowed myself to be recruited by the Venetians, into their service. Then we marched from one city to the next; in that district, that is, from Brescia to Peschiera on Lake Garda, there was an extremely beautiful fortress. The lake runs under it.

I got sick there, for the wine in this country is very heady. I was sick for two months, but the Almighty helped me again, although otherwise many Germans died.

After three months, we marched with our company to Verona, which is not very fortified and is located on the border to Mantua but is a charming place.

The sepulchral monument of the old Hildebrand [from the Hildebrandslied], surrounded by an iron grille seven Klafter [about 1.8 meters x 7 = 12.6 meters] long and wide. The old man and the young man, as they then fought on the moor, sit on two large marble horses on the top of their sepulchral monument at the marketplace in the middle of the city, where it can be clearly seen, for he held his court there.

After four months, from Verona to Verolanuova, which is under Milanese rule. There are good vineyards and grain fields everywhere.

In this year, 1625, from Verolanuova back to Brescia. Here we decamped and marched to Val Camonica. The main headquarters was at Edolo. [Peter Eppelmann, Reichsgraf von Holzappel, called] Melander, who was the general, was quartered there, and I was in his regiment under Captain Wortenburgk [?Wartenberg].

From Camonica we marched to Veltlin [Valtellina], where our enemy, the Spanish King, was. When Count Oppenheim arrived, he fired on us heavily with cannons and drove us out of Veltlin from our east and we had to retreat to Tirano. As we were located at Riva, we wanted to occupy the same castle. The Pope fell for the trick and was quickly handled. In that year, 1625, we were dismissed. There were two of us, my comrade Christian Kresse from Halle [and I]. We went together to Como, Milan, Pavia, Modena, Padua, and Parma. There we enlisted again. There we met a lute maker, a good German, who bought us many a good drink. The same person got me work. When I came from guard duty, I worked as a craftsman and made good money. We stayed there for twelve months. From there, we marched with our company to Piacenza, which belongs to the duke of Parma and is a splendid, beautiful city. Parmesan cheese is made in this land. We had been there for six months when we were dismissed. So we went back to Modena, Bologna, and Pavia, thoroughly beautiful land.

I must report here something of how this land is farmed. First there are fields six Klafter [about 1.8 meters x 6 = 10.8 meters] wide, then there are two Klafter free where grass grows. In the middle of the grass area are silk trees, that is, mulberry trees. Wine grapes are planted under the trees and railings made on both sides with rods. The grapes grow high on these. Throughout Italy, deep ditches are made next to the road on both sides; at a number of points, bridges are built across them. When rice is sown, the field is filled with water after sowing so that it is entirely covered as if it were a pond, and it is left that way to grow. Bitter oranges, figs, lemons, limes, and almonds all grow in that land, a lovely land. It is a little cold for two months and snow may fall, but as soon as the sun is as high as the trees, the snow has melted. In this way, cultivation of grain, wine grapes, wood, and meadows all takes place side-by-side, for they make their wood from the mulberry trees in fall, chopping the branches off, making bundles of wood, and selling twenty-four pounds for a groschen, that amounts to two Kreuzer [ about 4.2 pennies] at home.

From Pavia to Milan, a nice road, in a straight line. From Milan to Como. Milan is a beautiful city. The fortress is in front of the city, in a straight line, very well fortified. There we begged, because our money was gone. From Como to Bellinzona, because this land all belongs to the Spanish king, namely, Pavia, Milan, and Como.

Bellinzona is the first city in Switzerland, and Italy ends there. But everything is welsch, and the mountains start again. The same mountain that must be climbed over is called Gotthard. It takes a whole day to get over. In the middle of the mountainside stand a chapel and an inn, for if a person dies or freezes to death—it is terribly cold and there is much snow on the mountain in winter and summer—he is thrown in the chapel. But in the inn, needy people are given a piece of bread and a half measure of wine, and they are allowed to go on, or are kept overnight, if they cannot continue. For if a person sits down on this mountain, he is immediately dead.

At midday, we arrived at the inn. The weather was bright and beautiful; we ate our piece of bread and whatever we were given. We immediately left. Then such a storm came up that we could not even see each other. So I went first, all downhill, until [we got to] a bridge called the Devil’s Bridge. It leads from one mountain to the next, and water runs under the bridge, falling from one precipice to the next, as high as a church tower. If a person falls, that is the end of him, even if he is worth a thousand people. That is how I lost my comrade; I still do not know where he went.

At the foot of the mountain is a village called Andermatt. Then to Altdorf with the Linth [River]. There I embarked on a ship and traveled across the lake. The chapel that William Tell jumped out of and where the Swiss got their freedom can still be seen there.

As our good luck was done, I went to Brugg. Everything there was German again. To Königsfelden, a beautiful monastery, then to Schaffhausen. In Schaffhausen, I got so much by begging that I decided to buy shoes, but I went into the tavern beforehand. There the wine was so good that I forgot about the shoes. I tried on my [old] shoes with willows and walked to Ulm on the Danube.

On April 3, 1627, I enlisted in the [Gottfried Heinrich zu] Pappenheim Regiment in Ulm as a private because I was completely down-and-out. From there we marched to the muster location in the Upper Margraviate Baden. I stayed in quarters there, ate like a pig and drank, so it was good.

Eight days after Easter, on the [Feast of the] Holy Trinity, I married and wed the virtuous Anna Stadler from Traunstein in Bavaria.

On St. John’s Day, our standard was nailed to the staff at Rheinbischofsheim. There we embarked with the entire regiment on a ship and sailed to Oppenheim, where we disembarked. However, a ship collided with us underway, causing it to break up, and a number of people drowned.

From Oppenheim to Frankfurt, through the Wetterau and Westphalia, to Wolfenbüttel in the Braunschweig area. We encamped there, built redoubts, and fiercely attacked the city using water dams and structures so that they had to surrender. There my wife was sick for the entire siege, as we stayed there for eighteen weeks. On Christmas Eve, 1627, they left, but for the most part they enlisted.

About 200 men from the Altmark came to transport the sick and wounded. I put my wife aboard, too. Then we marched to the Altmark. Our headquarters was in Gardelegen. Our captain, Hans Heinrich K[i]elmann, was transferred with his company to Salzwedel.

There I got sick, and my wife was healthy again. I was down for three weeks. Four weeks after my illness, we were ordered to Stade, below Hamburg, and I was sent along.

At that time, my wife went into labor, but the child was not yet full-term and died immediately. May God grant him a happy resurrection; it was a little son.

We encamped before Stade. On Good Friday we had enough bread and meat, and on holy Easter we could not have even a mouthful of bread. We decamped in 1628 and remained in our quarters again for the summer.

After that, we marched with our company to Stendal, where we also had good quarters. In 1629 Lieutenant-Colonel [Carl I] Gonzaga, Prince of Mantua, took 2,000 men from the regiment, for the regiment had 3,500 men, and marched to Pomerania; we encamped before Stralsund. But they would have shown us the way out, if we had stayed a day longer. The baggage remained behind in quarters.

This time, while I was away, my wife was again blessed with a young daughter. She was baptized Anna Maria in my absence. She also died while I was away. May God grant her a happy resurrection.

From Stralsund we all traveled up the river, called the Świna, with two ships and into the territory of the Kashubian people, a wild land, but with outstanding husbandry of all kinds of animals.

There we did not want to eat any more beef; instead, it had to be geese, ducks, or chickens. At the place where we stayed overnight, the landlord had to give each of us a half Thaler, but amicably, because we were satisfied with him and left his cattle in peace.

Thus, we marched back and forth with 2,000 men, every day new quarters, for seven weeks. We stopped for two days at Neustettin [Szczecinek]. There the officers were well provided with cows, horses, and sheep, because there were plenty of all of them.

From there to Spandau, a mighty pass where not more than one company was let through at the same time. Shortly after we once again arrived in the March [frontier area] at our quarters, we set out in 1629 with our entire regiment and marched to Wetterau.

There my wife was once again honored with a young daughter, who was baptized Elisabet. After twenty weeks, we decamped and marched to Westphalia. Our quarters were in Lippstadt; we stayed there over the winter. In that land, the people, men and women, are big and strong; the land is fertile, and a great deal of livestock is raised. In the countryside, there are almost only individual farms; they have their cultivated fields, wood, and meadows all close to the house.

In that land, the people bake loaves of bread that are as big as grindstones, but square. The bread has to stay in the oven for twenty-four hours. It is called pumpernickel, but it is good and tasty bread, completely black.

In 1630, we decamped there and marched to Paderborn. Lippstadt is next to a river with many ships, called the Lippe. From Paderborn to Niedermarsberg, which is situated on a high mountain. Then to Goslar in the Harz and to Magdeburg.

We moved to villages and blockaded the city. We stayed out of action in villages for the entire winter, until spring of 1631. We captured several entrenchments in the forest before Magdeburg. Our captain, along with many others, was shot dead there in front of an entrenchment. On one day we captured seven entrenchments. After that we moved in very close, and blocked everything with entrenchments and approach trenches, but it cost a lot of men.

On March 22, Johann Galgort was introduced as our captain; on April 28, he was shot dead in an approach trench. On May 6, Tilge Neuberg was introduced to us once again. He had our company for ten days, but then he resigned.

On May 20 we attacked in earnest, stormed in, and then took the city. I stormed into the city without any injuries, but when inside the city at the Neustadt gate I was shot twice through my body; that was my booty.

That happened on May 20, 1631, at 9 o’clock.

Afterwards, I was taken to the camp and my wounds bandaged, for I had been shot once through the stomach, and a second time through both shoulders so that the bullet lay in my shirt. Consequently, the field surgeon tied my hands behind my back so that he could apply the cutting tool. Then I was taken half dead to my hut. However, I was very sorry that the city was so badly burned because it was a beautiful city and it was my fatherland.

Once I was bandaged, my wife went into the city even though it was burning everywhere; she wanted to get a pillow and cloths for bandages and also for me to lie on. Consequently, I had my sick child lying next to me. Then a great clamor arose in the camp: the buildings were all collapsing, and many soldiers and women who wanted to pilfer had to stay in them. Because of that, I was more worried about my wife because of the child than about my wounds. However, God protected her. She came back from the city after an hour and a half with an old woman. She had brought her along with her; the woman was a sailor’s wife and had helped her carry bed linens. She also brought me a large jug containing four measures of wine, and besides that had found two silver belts and clothes that I sold for twelve Thaler in Halberstadt. In the evening, my comrades came by and each of them honored me with something, a Thaler or a half Thaler.

On May 24, Johann Philipp Schütz was introduced to us. I, together with all the [other] wounded, was taken to Halberstadt. There we were moved to villages. Three hundred men from our regiment were placed in one village, and all have recovered.

I had a very good landlord there who did not give me any beef but only veal, young doves, chicken, and birds. After seven weeks, I was again fresh and healthy.

Beyond that, my little daughter Elisabet died there. May God grant her a happy resurrection.

After seven weeks, we were picked up again by the army. When the Swedish army arrived at Havelberg, we moved to Tangermünde and Werben on the Elbe. There the Swedish army dug itself in. The heat was so terrible that a drink of water was expensive then.

[….]

Source: Jan Peters, ed., Peter Hagendorf – Tagebuch eines Söldners aus dem Dreißigjährigen Krieg. Herrschaft und soziale Systeme in der Frühen Neuzeit 14. Göttingen: V & R unipress, 2012, pp. 100–05. Republished with permission.

Further Reading

Johannes Burkhardt, Der Dreißigjährige Krieg. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1992.

Benigna von Krusenstjern and Hans Medick, eds., Zwischen Alltag und Katastrophe. Der Dreißigjährige Krieg aus der Nähe. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 2001.

Markus Meumann and Dirk Niefanger, eds., Ein Schauplatz herber Angst. Wahrnehmung und Darstellung von Gewalt im 17. Jahrhundert. Göttingen: Wallstein, 1997.

Herfried Münkler, Der Dreißigjährige Krieg. Europäische Katastrophe, deutsches Trauma 1618–1648. Berlin: Rowohlt, 2017.

Georg Schmidt, Der Dreißigjährige Krieg. 6th edition. Munich: C. H. Beck Verlag, 2003.

Peter H. Wilson, The Thirty Years War: A European Tragedy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011.