Carl Munde, My Escape from Dresden to New York in 1849 (1867)

Abstract

Carl Munde (1805-1887) came from Freiberg in Saxony and worked as a language teacher before making a name for himself as a hydropath (“water doctor”). As a member of the radical-democratic Fatherland Association and a local gymnastics association in Dresden, he was involved in the March Revolution of 1848/1849 against the existing power relations in the German Confederation. He was wounded and fled with his family, first to Antwerp and finally to the United States. In this article he recalls the circumstances of his escape from Germany to New York. He succeeded in establishing a clinic for hydrotherapy in Massachusetts. After an amnesty for the revolutionaries was declared, Munde returned to Germany with his family in 1866, before finally settling in the then Austrian town of Gorizia.

Source

The events of 1849 in Dresden are well known. I was a member of the central commission of the patriotic associations and a city councilor. In this capacity, and as a member of the commission of the Dresden Militia in my role as commander of the legally organized, albeit thoroughly democratic, gymnasts’ train-band, I consequently participated in all resolutions taken by these bodies. Meanwhile I dared, with my train-band—the only one to advance in closed order on that fateful second of May led by its regular officers—to act in support of the people.

On the fifth of May, having just briefly addressed the soldiers at the barricade nearest to the palace, I came under heavy fire from the palace and the chapter houses when I stepped down from the barricade and walked amidst the shooting back to the Hotel de Pologne whence I had come. The bullets whistled past to my right, left and above me, probably fifty of them before one hit me. And hit me it did! I plainly felt it go through my left calf, but nevertheless continued with the aid of a cane, which I was carrying in my right hand because of an ankle twisted on the barricade, to walk the few steps to the entrance of the Hotel de Pologne, where I fell into the arms of my men. The blood loss was so great that I soon felt my senses leave me and had only just enough time to order them to carry me through Banker Kaskel’s house to the Lion Apothecary, where a bandaging station had been set up.

When I came to, I found myself bathed in cold sweat, lying on a pile of straw on the floor of the apothecary, to my right and left other more or less gravely injured men. A young doctor kneeled at my feet and examined my wound, my naked foot in his hand. I asked whether there were any broken bones and he answered that there were not. The next day, however, my servant Hingst brought me my stocking, which had some bone splinters sticking to it. He told me he had already washed out a number of them. Later it was discovered that my fibula had been split in two and half my shin bone was gone; that is, I had taken the last steps after being shot on only half a shinbone. The leg quickly swelled and made examination difficult.

After sending a few lines to my wife through a friend, I was carried in a sedan chair through the Scheffelgasse and, since it was blocked by a barricade at Wallstrasse, through what is now the Hotel Meisel to my home on Oberseergasse, where my loyal spouse welcomed me with tears of joy and pain. What joy that I at least did not arrive home dead!

I lay there for three days with no other bandages than wet cloths, which I often moistened with fresh water, and without any food. […] Meanwhile the battle grew fiercer and fiercer. Finally, on the afternoon of the eighth, my friend Dr. Herz came to me and said that he feared we would not be able to resist for much longer; if he was not completely mistaken, the city would be captured that very night. This moved me to send my servant for a wagon to take me to one of the neighboring villages. After much effort, he found a farmer who was willing for money to take me with him to Tharand.

And so a mattress was laid upon the floor of the wagon, I was lifted in and a few articles of clothing and my saber were placed next to me; then my wife got into the wagon with our three- and-a-half-year-old child and one of my older sons, Albert, aged around fifteen, and finally the farmer himself, and now, accompanied by my four riflemen with loaded muskets, we traveled through the Plauen valley towards Tharand. I sent my escort back one hour outside Dresden and arrived without incident around eleven in the evening in Tharand, where I was welcomed by a merchant’s widow of our acquaintance who agreed to take us in and tend to me.

Early in the morning I sent for a surgeon to examine my wound and bandage it properly. He had just inserted the probe when my son burst into the room with the news that Dresden had fallen, and that masses of auxiliaries and refugees were walking along the road. He had spoken to Heubner, who would be here presently.

The latter soon followed and asked in a scarcely recognizable, hoarse and gravelly voice, “How are you doing, Munde?”

“Poorly, as you can see!”

“It is all over. You can’t stay here. Come with us in the government wagon.”

“I cannot sit and must keep my leg elevated.”

“Fine, then I shall requisition a farmer’s cart for you; it will be here soon.”

“What are you planning to do.”

“We’re heading for Freiberg.”

“You musn’t. You can’t stay there.”

“We shall try; we are 10,000 men with the auxiliaries.”

“Three-quarters of them are on the run. Make sure you get out of here.”

“I must leave. Farewell. I’ll see you in Freiberg!”

The poor fellow did not know what fate awaited him in Chemnitz, which he reached dead-tired the next night with Bakunin and Martin. We saw each other again, but not in Freiberg, after I had spent seventeen years in America and he ten years in Waldheim! I saw Bakunin again in New York in 1861, after his successful escape from Siberia.

[…]

Soon I left everyone behind me. In Grüllenburg I met the vanguard of the small army that was going—I would not say hastening, since they came too late— to the aid of Dresden. I summoned the commanding officer and told him that he could turn around again, because the government wagon drawn by four horses was following just behind me. He did not believe me. It was Prößel from Chemnitz. I saw him again in New York, where he kept a hotel on Beekman Street.

[…]

And so another night fell that brought me little rest, which I spent awake in pain and worry. Around six o’clock in the morning, through the window from my bed I saw the approach of Saxon cavalry and mounted artillery coming down over the Hammerberg. The city gates were occupied and cannon were rolled onto the market square on which a stone still marks the spot where Kunz von Kauffungen, the abductor of princes, was beheaded. Anyone deemed at all suspicious was immediately arrested. Fortunately the police had too much to do in the center of the city to worry about the suburbs or me. And so I lay undisturbed the entire day, unsure what would become of me. Many of my comrades visited me on the first day. All of them promised to procure me a wagon. Not one was able to keep his promise. All of the horses had been requisitioned by those fleeing. The next day, May 10th, I was visited by a miner by the name of Schüttauf who had traveled with me from Tharand to Freiberg and asked what he could do for me. I bade him go to Halsbrücke to see a relative of mine and ask him whether I could stay there for a few days, and if he received a positive answer to rent a wagon and come through the back door of the courtyard of the house at six-thirty on the dot to collect me. A picket of Saxon horsemen stood in the Wild Man Inn across the street. The wagon arrived on time. I bid farewell to my dear old mother and my sister. I never saw either of them again! My brother-in-law placed a mining official’s uniform cap on my head and draped an official’s coat around my shoulders, and so I was lifted up onto the light, open wagon; my son Albert sat down next to me and we took the well-known byways behind the city—the city of my birth— towards Halsbrücke one hour away.

There I was welcomed like a brother by my kinsman Ludwig and his friendly young wife and installed so comfortably that I would gladly have stayed longer, if only it had been possible. […]

We deliberated over where I could go. Ludwig’s wife mentioned her father who lived in Bräunsdorf and would likely be in a position to conceal me. The wagoner who had driven me was hired again, but this time with a covered wagon. When it was dark my mattress was laid inside again and I upon it, then some household goods were placed over me so that the whole thing looked as though someone was moving house, then the wagon was covered and we drove out into the night towards Bräunsdorf. Cousin Ludwig and Albert marched before and alongside the wagon.

We reached Bräunsdorf around two in the morning and stopped in front of the house of the old man, who replied after some knocking. He refused to take me in, since it could not remain a secret for even two days. At my request he handed me fifty taler in a roll through Ludwig. A further sum had been loaned to me by a noble friend in Freiberg, to whose help I already owed my life and my health thirteen years before. We were thus compelled to continue our journey. I had no idea where to go. Then I remembered Judicial Director Schiffner in Mittweida, as well as Deputy Müller of Taura. We drove on towards Haynichen and Mittweida, although I did not know how these two likeminded men could help me.

[…]

I will pass over the events of my journey up to Wolperndorf, the first village in Altenburg. It was the middle of the night when we arrived there. I was half asleep almost the entire time and only became fully conscious when the two men knocked on the gate of the Altenburg inn, loud enough to wake the entire village. All the noise failed to rouse anyone: It was clear that the innkeeper did not wish to open up because of the many mostly armed refugees, from whom he could scarcely earn any money. Finally the men climbed over the high wall into the courtyard, and after much effort and grappling with the chained dog, who attacked them ferociously, they succeeded in getting the innkeeper and his daughter to come to the door.

I heard the innkeeper refuse to take me in, and then how he finally relented after many blandishments, notably from his own daughter, and agreed to open the gate and let the wagon drive into the courtyard.

[…]

In the afternoon Rittler came at the appointed hour, bringing his nine-year-old son Anton with him to make the wagon journey look more like a family affair. Having learned from experience, we admonished our friends in Wolperndorf to reveal my presence to nobody whatsoever and departed after heartfelt goodbyes and full of gratitude for all the kind people there. Only once did a gendarme inquire, having seen Albert, but received the answer that the young man was a visitor at the parsonage; as far as they knew he was the cousin or even the brother of the pastor’s wife. After Rittler had persuaded himself that I spoke English fluently and with a good accent—Englishmen had occasionally taken me for a fellow countryman—we agreed that I would be introduced into the doctor’s house as an American, namely Mr. Charles Murray (we had to keep the initials C. M. because of my linens etc.), who had broken a leg when the wagon turned over, and was in need of treatment. I was allowed to speak only occasional broken German, except when we were alone. The doctor‘s wife had spent several years in England and spoke English well, so that she could act as an interpreter, and nobody would guess that Mr. Murray of New York was actually none other than Dr. Munde of Dresden. In order to render the fact more plausible, a young Englishman who was sojourning in Altenburg and who visited the Rittlers frequently was to be introduced to me. And that is what happened, and with great success, despite all the hazards to which our plan was exposed. Rittler had arranged that we would arrive in Altenburg, which was occupied by a battalion of Prussian, after dark.

[…]

To keep the police off my trail, during the very first days I wrote a letter to my wife which I sent to a friend who was a member of the Frankfurt parliament requesting he take it to the post there. In this letter I notified my wife that I had arrived safely in Frankfurt and was about to leave for Baden, where I had been offered a command. The wound on my right foot was insignificant. The letter was naturally opened, and soon afterward I saw from the wanted poster that I had a slight gunshot injury to my right foot. That wanted poster contained twenty-two of the most incriminated names, among which it was no shame to be included, since they encompassed men like Richard Wagner, Professor Semper, Dr. Köchly, Councilor Todt, Leo von Zichlinski, Marshal von Biberstein etc.

[…]

A few days after the departure of my wife Rittler in fact brought me a blank Royal Saxon passport along with a completely prepared passport belonging to one of his friends, who was in the midst of emigrating to America with his family, issued by the same authority, so that the document could be filled out properly as I wished. The official who sent me the passport (not the first that Rittler had received from him) was later investigated, but managed to avoid prison thanks to his wife‘s cleverness and presence of mind, since she caused the policeman pursuing him to fall into the cellar and locked him in. He settled in America. It was my good fortune that not all democratically minded officials were as timorous as friend Flügel, otherwise, despite all the love and friendship otherwise shown to me, I would surely have been doomed. May this knight in shining armor who, as far as I know, lives in Philadelphia, not disdain my belated thanks here. My family and I have blessed him and his one thousand times over.

While friend Rittler was arranging my onward journey in this manner, other friends supplied me with the necessary money, of which I collected more than I needed at that moment. My doughty publisher not only sent me several hundred taler, but also provided me with substantial credit in Brussels. As soon as I was able to move with a crutch and a walking stick I was eager to travel. An inner voice told me that I was in danger and could be discovered any day. The upright brewer Ruoff had promised me his horses and carriage, and the day for my departure was set. He came the evening before to tell me that his carriage had not yet returned and that he only had one horse at home, so that I would have to wait another day. I expressed my concern that one day longer could be harmful to me; I could not suppress the presentiment that the police had finally become aware of my presence and would search the house to see who the mysterious Englishman, of whom they had doubtless heard something, actually was. After some reflection, he decided spontaneously, “Alright then, I will give you my saddle horse and stay home tomorrow. The coach should be there at four in the morning.” I hope that the thought of my rescue helped to brighten the final hours of this righteous man, which struck far too soon.

The wagon found us all prepared well before four o’clock. The good doctor’s wife had seen to breakfast, and as much as I wanted to be on my way, it was painful to bid farewell to this devoted friend, who had done so much for me. The doctor accompanied me as far as Halle. The police arrived at his house that very afternoon, alas not for the last time, for he was later dragged into the matter and, after sitting in prison for several months, his health all but ruined, he was also forced to emigrate to America with his large family, where I had the opportunity to repay some of my debt to him, for an entire lifetime would not be enough to repay it in full!

We traveled to the nearest railroad station in Weißenfels. I dared not go to Leipzig, for fear of being recognized. When we stopped at a village tavern along the way we met the first Prussian gendarme. The elegant carriage, with the sumptuous harnesses and the liveried coachman impressed him so greatly, however, that he merely greeted us politely, to which I replied in a jovial manner, as great gentlemen are wont to do.

Doctor Rittler bought second-class tickets and, approaching the carriage surrounded by police and doffing his cap, said “If you please, My Lord, I have the tickets.” To which I responded, “Good, my dear Doctor,“ and set about descending from the carriage with his and Albert’s help, in order to walk to the coach of the steam train intended for us. Installed there with the aid of a sort of bridge made of wood and black canvas on which I could stretch out my leg, I brought my dagger into a position from which I could easily access it if necessary.

[…]

I had made my decision, and Rittler knew it. He had a letter from me to my wife in which I said farewell in case it came to the worst and offered some advice with regard to her and the children’s future. Unfortunately, through some misunderstanding, this letter reached her before she had heard that I was safe, and was the occasion of much pain and weeping. She kept it for many years until it, like nearly all the precious mementoes of that difficult time, fell prey to the fire that struck us in Florence in the autumn of 1865.

I feared Halle greatly, for I had heard that the Dresden police had established a commissioner there. To be sure, I had done everything possible to make myself unrecognizable. My beard was gone, I was not wearing spectacles, and I kept myself shrouded in a gray greatcoat; very bent, I was pale and much thinner, and I wore a green hunter’s cap with a double-wide visor that hid the upper part of my face (no one had ever seen the lower part without a beard) and also hid the shape of the back of my head. My hair, cut short, had also become noticeably lighter in recent weeks so that instead of a large, robust man of forty-four, people must have seen a broken old man of sixty-eight years. And yet it was possible for some to recognize me, perhaps my son, and perhaps even my loyal friend who had already attained some renown—or some notoriety—as a forwarding agent on the “underground railroad,” as one of the military authors who wrote about the May events put it with regard to myself.

[…]

Another handshake, a “Farewell, My Lord, please write soon,” a “Farewell, dear Doctor, a thousand thanks for all your efforts,” and the train pulled out without a hair of my head having been harmed in Halle. In Magdeburg we had to wait some time before the train left for Hanover. I limped to the restaurant with my crutch and cane; the pains were so sharp that sweat ran down my face as I walked the gauntlet of assembled gendarmes and soldiers. In the restaurant, a tall, strongly-built gentleman of about forty-five years wearing a gray riding coat approached me and asked whether he could help in any way. I took him for the owner and asked for a chair and a glass of water. He led me to an armchair standing in the dark, ordered a glass of water and offered me a pinch from a golden box. When I accepted and expressed my pleasure he offered me the entire box.

“You can return it in Hanover,” he added. I thanked him but refused.

I now knew it was the aulic councilor and felt much relieved to find another friendly soul there, apart from my boy. We arrived at Hanover quite late in the evening, where the brawny servant from the Hotel du Rhin carried me on his back and deposited me in our room on the second floor. […]

The next day we passed Aachen and the Belgian border. As we rode past the Belgian lion it was if a heavy weight had been lifted off my shoulders. Indeed, I felt so light and happy that I could gladly have embraced even my pursuers.

In Verviers our passports were examined and our bags searched. Neither the bearskin-capped gendarmes nor the customs officers had any objections to Mr. Christian and his son, and in the evening we landed in Brussels at the Hôtel du Grand Café, which had rightly been recommended to me, and where I surrendered myself to the protection and care of good old Mr. Rosart. I stayed there for more than six weeks, at first under my assumed name but towards the end under my own name, as I will soon relate.

[…]

It was my original intention to settle in England, and that was also written in my wife’s passport. Through a coincidence, however, I made the acquaintance of the Inspecteur général de l’Université de Bruxelles, Mr. van Hasselt, who, after several discussions on education and teaching methods, offered me a professorship at the university of Liège. My friends advised me not to accept. The educational institutions were all under the influence of the Jesuits, and they would not rest until they had pushed out all the Protestants. Clemson put an end to any doubts.

“Nonsense,” he said, “to even consider remaining in a country where one person was always grabbing the food from another’s mouth. Go to America, where there is more than enough of everything. I shall write to my father-in-law and you will want for nothing.”

And so we embarked from Antwerp on the Scheldt on August 20th, and landed on the last day of September at the foot of Fulton Street in New York to begin our lives again in the New World.

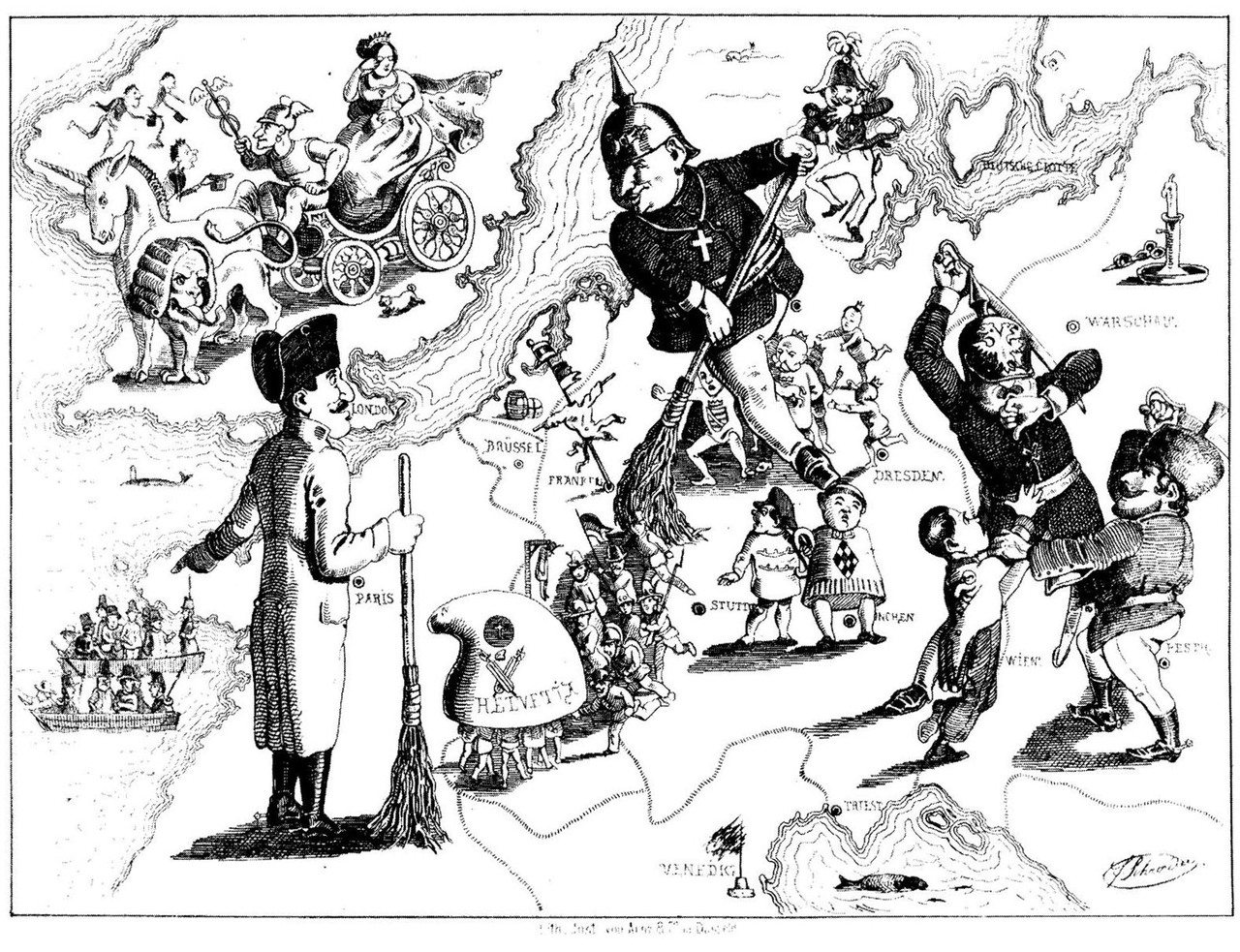

Source: Carl Munde, “Meine Flucht von Dresden nach New-York im Jahre 1849,” Die Gartenlaube, edited by Ernst Keil, nos. 10 and 11. Leipzig, 1867, pp. 152–56 and 168–71.