Stefano Jacini, On the Emigration of Italians to Germany (1915)

Abstract

Count Stefano Jacini (1886-1952) was an Italian lawyer and publicist who later made his political career as a member of parliament, minister and senator. In this excerpt from an article that appeared in the journal Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv in 1915, he describes Italian labor migration to Germany at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Source

[…]

The workers depart in the early spring, generally in large groups. In Italy they have the right to purchase tickets at a reduced price, even if traveling alone. Since they have to form groups at the border in order to receive the foreign price reductions, and since men from the same village are generally traveling to the same centers of employment, these larger groups usually already form in Italy. As a rule, such groups are composed of young men wearing typical emigrant attire: wide velvet trousers, red belts, colorful shirts, dark jackets – clothing not especially characteristic of any Italian province, but which emigrants have adopted almost as their trademark, although to my knowledge the origin is French. A few mothers and sisters travel with them, but more numerous are the boccias (adolescent boys), who, like the underage girls, are one of the chief dangers and chief nuisances of Italian emigration, and whose departure is limited and regulated by strict laws.

Foreign enterprises are forbidden from recruiting workers in Italy, but many do so nonetheless, either by acquiring state-issued permits (which are subject to strict, always revocable conditions), or covertly through confidential agents who know how to evade the Italian police. In both cases, recruitment is difficult: Italian workers are quick to make decisions, and the agents lure them away from others at the border, during the journey and abroad by all manner of enticing promises. It thus happens that of 100 workers recruited in Italy, scarcely 50 arrive at their intended destination, regardless of how much surveillance there is of the means of transportation. As for the workers who are not recruited, they mainly head for the well-known centers of employment, with which they are already familiar from the letters of their friends or relations. Although the Italian worker often appears self-conscious and sometimes exhibits an unkempt appearance, he is neither the one nor the other: for example, he has a good instinct for choosing work and knows how to look after himself without paying too much attention to official announcements.

The means of transportation for Italian emigrants have improved significantly in recent years: with the help of the “Society for Italian Workers Emigrating to Europe,” which will be discussed later, the foreign railroad companies have set up special trains that bring the workers regularly and directly from the borders to the important centers of employment (e.g. Ala-Dortmund), so that such a journey at a greatly reduced price generally proceeds more quickly than for the usual traveler. Moreover, special announcements in particular – always in connection with the abovementioned aid society – draw attention to the best travel connections, and currency exchanges, hostels and employment information bureaus are available at the borders. It is also thanks to these well-developed organizations that emigrants nowadays need only 40 hours to travel from Piedmont to Westphalia, whereas in 1900 the journey took at least 4 days. Other special institutions relating to border traffic have been introduced recently: for example, emigrants are permitted to bring a supply of national products (salami etc.) with them to Germany or other countries in order to spare them the penalties to which they might otherwise unwittingly subject themselves.

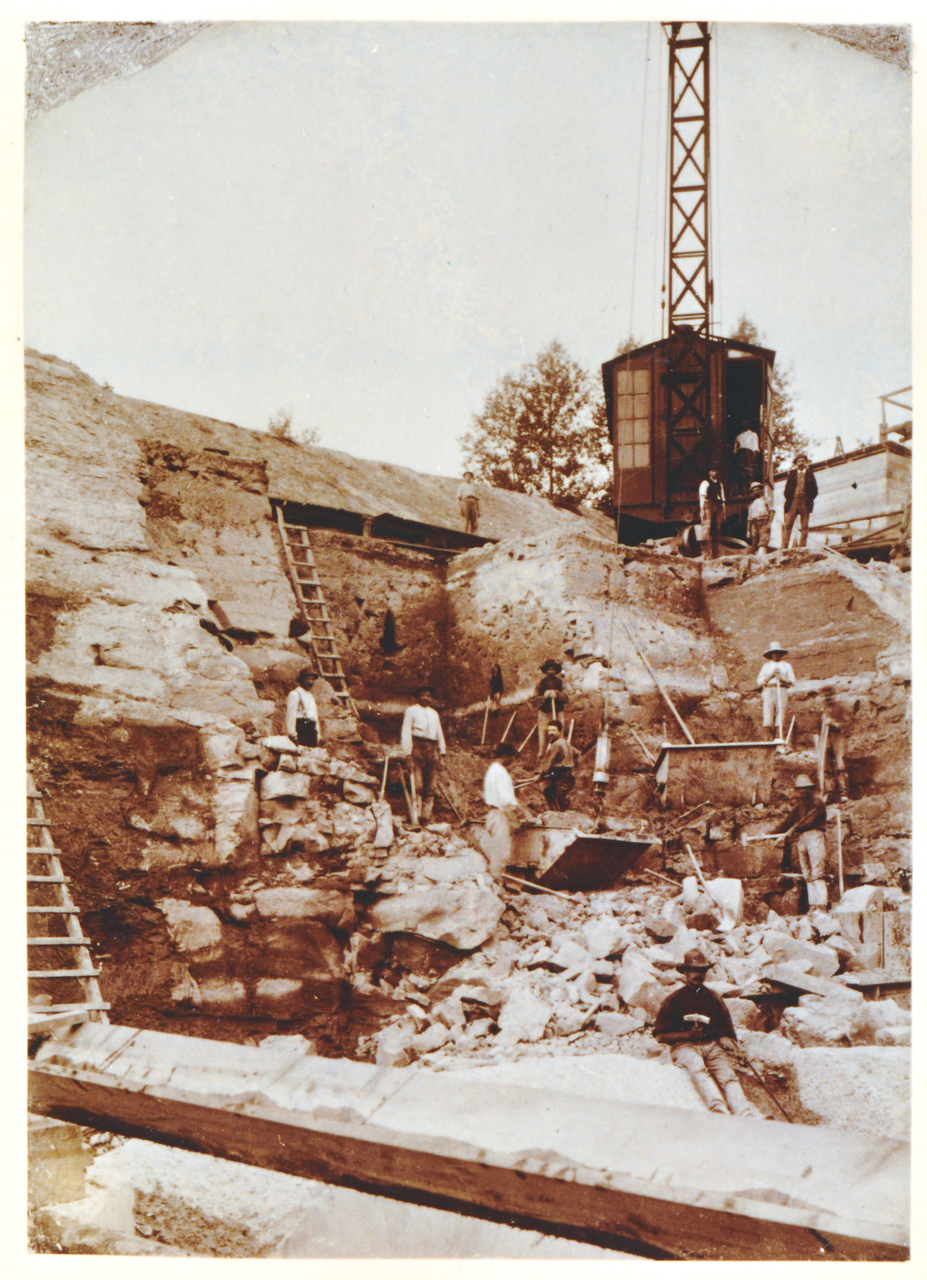

Let us now look at the mass of workers, such as we find in nearly all towns in Germany. Because nearly two-thirds of the workers who emigrate to Germany perform unskilled labor, some German economists believe it justified to judge this labor in purely quantitative terms and compare it to that done by Negroes and Chinese. They no longer distinguish the individual from the proletarian mass, considering the Italian element to be a necessary factor for attaining certain ends, as “wage slaves” whose personality is irrelevant as such and for progress in the host nation. They regard the “uncivilized” Italian emigrants as an amorphous mass to be replaced at will, and find this assumption to be justified by a series of traits that characterize the Italian workers: for example, the high percentage of illiterates, the commonness of deficient hygiene, the low level of interaction with the rest of the population, the exceedingly simple and sometimes insufficient food, the choice of the poorest and least salubrious housing, etc. If, however, one examines these characteristics more closely, such judgments prove wholly superficial. In particular, the notion of “quantitative” emigration inspired by misery and the acceptance of wages that barely cover the necessities of everyday life is untenable. As we stressed above, emigration from Italy – allowing for the few exceptions – is not caused by hunger, but rather yields a net profit of around half a billion. And must labor that is also irreplaceable for many enterprises truly be regarded as unskilled? For example, Italian workers are not hired for tunnel-building and in the iron mines simply because they are cheap. Rather, such laboring masses should not be compared to beasts of burden if a host of state agencies and private institutions study their actions, respond to their grievances and recognize their rights – something that applies or should apply to all of Italian emigration.

[…]

Source: Stefano Jacini, “Die italienische Auswanderung nach Deutschland,” Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 5 (1915), pp. 128-30.