Speech by Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler before the Reichstag (October 6, 1939)

Abstract

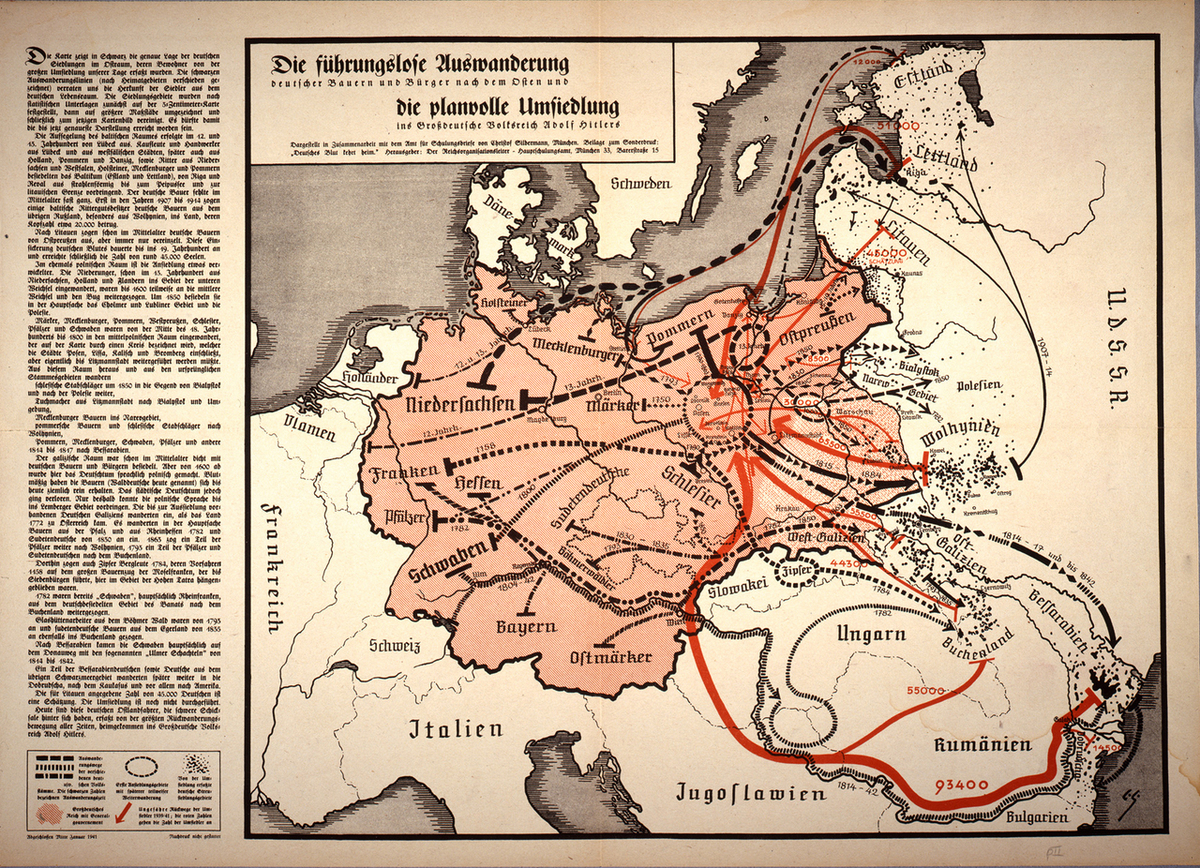

In contrast to Hitler's secret speech of August 23, 1939, in this speech before the Reichstag (parliament), which is reproduced here in excerpts, he exercises the greatest restraint with regard to the true intentions of the Nazi war of conquest in Eastern Europe. He denies plans for further conquests and mentions the goal of “order and settlement of the Jewish problem” only in passing. Shortly after the rapid victory over the Polish army, a good portion of the speech consists of boasts about the achievements of the German Wehrmacht and Hitler himself in this process. Equally conspicuous is his attempt to justify the sudden alliance with the Soviet Union, the former main enemy of National Socialism. He describes a “new order of ethnographic relations” as the “most important task,” which is to be created through the resettlement of minorities and would “eliminate at least some of the material for European conflict.”

Source

[…]

Under these blows their State [Poland] has crumbled to pieces in a few weeks and is now swept from the earth. One of the most senseless deeds perpetrated at Versailles is thus a thing of the past.

If this step on Germany’s part has resulted in a community of interests with Russia, that is due not only to the similarity of the problems affecting the two States, but also to that of the conclusions which both States had arrived at with regard to their future relationship.

In my speech at Danzig I already declared that Russia was organized on principles which differ from those held in Germany. However, since it became clear that Stalin found nothing in the Russian-Soviet principles which should prevent him from cultivating friendly relations with States of a different political creed, National Socialist Germany sees no reason why she should adopt another criterion. The Soviet Union is the Soviet Union, National Socialist Germany is National Socialist Germany.

But one thing is certain: from the moment when the two States mutually agreed to respect each other’s distinctive regime and principles, every reason for any mutually hostile attitude had disappeared.

[…]

For many years imaginary aims were attributed to Germany’s foreign policy which at best might be taken to have arisen in the mind of a schoolboy.

At a moment when Germany is struggling to consolidate her own living space, which only consists of a few hundred thousand square kilometers, insolent journalists in countries which rule over 40,000,000 square kilometers state Germany is aspiring to world domination!

German-Russian agreements should prove immensely comforting to these worried sponsors of universal liberty, for do they not show most emphatically that their assertions as to Germany’s aiming at domination of the Urals, the Ukraine, Rumania, etcetera, are only excrescences of their own unhealthy war-lord fantasy?

In one respect it is true Germany’s decision is irrevocable, namely in her intention to see peaceful, stable and thus tolerable conditions introduced on her eastern frontiers; also it is precisely here that Germany’s interests and desires correspond entirely with those of the Soviet Union. The two States are resolved to prevent problematic conditions arising between them which contain germs of internal unrest and thus also of external disorder and which might perhaps in any way unfavorable affect the relationship of these two great States with one another.

Germany and the Soviet Union have therefore clearly defined the boundaries of their own spheres of interest with the intention of being singly responsible for law and order and preventing everything which might cause injury to the other partner.

The aims and tasks which emerge from the collapse of the Polish State are, in so far as the German sphere of interest is concerned, roughly as follows:

1. Demarcation of the boundary for the Reich, which will do

justice to historical, ethnographical, and economic facts.

2.

Pacification of the whole territory by restoring a tolerable measure

of peace and order.

3. Absolute guarantees of security not only

as far as Reich territory is concerned but for the entire sphere of

interest.

4. Reestablishment and reorganization of economic

life and of trade and transport, involving development of culture

and civilization.

5. As the most important task, however, to

establish a new order of ethnographic conditions, that is to say,

resettlement of nationalities in such a manner that the process

ultimately results in the obtaining of better dividing lines than is

the case at present. In this sense, however, it is not a case of the

problem being restricted to this particular sphere, but of a task

with far wider implications, for the east and south of Europe are to

a large extent filled with splinters of the German nationality,

whose existence they cannot maintain.

In their very existence lie the reason and cause for continual international disturbances. In this age of the principle of nationalities and of racial ideals, it is utopian to believe that members of a highly developed people can be assimilated without trouble.

It is therefore essential for a far-sighted ordering of the life of Europe that a resettlement should be undertaken here so as to remove at least part of the material for European conflict. Germany and the Union of Soviet Republics have come to an agreement to support each other in this matter.

The German Government will, therefore, never allow the residual Polish State of the future to become in any sense a disturbing factor for the Reich itself and still less a source of disturbance between the German Reich and Soviet Russia.

[…]

What then are the aims of the Reich Government as regards the adjustment of conditions within the territory to the west of the German-Soviet line of demarcation which has been recognized as Germany’s sphere of influence?

First, the creation of a Reich frontier which, as has already been emphasized, shall be in accordance with existing historical, ethnographical, and economic conditions.

Second, the disposition of the entire living space according to the various nationalities; that is to say, the solution of the problems affecting the minorities which concern not only this area but nearly all the States in the southeast of Europe.

Third, in this connection: An attempt to reach a solution and settlement of the Jewish problem.

Fourth, reconstruction of transport facilities and economic life in the interest of all those living in this area.

Fifth, a guarantee for the security of this entire territory, and sixth, formation of a Polish State so constituted and governed as to prevent its becoming once again either a hotbed of anti-German activity or a center of intrigue against Germany and Russia.

[…]

Source: Text of Chancellor Hitler’s Speech before the Reichstag, October 6, 1939, International Conciliation No. 354 (November 1939), pp. 507-09; 520-21.