Report on the Experiences of a Captured Christian (1623)

Abstract

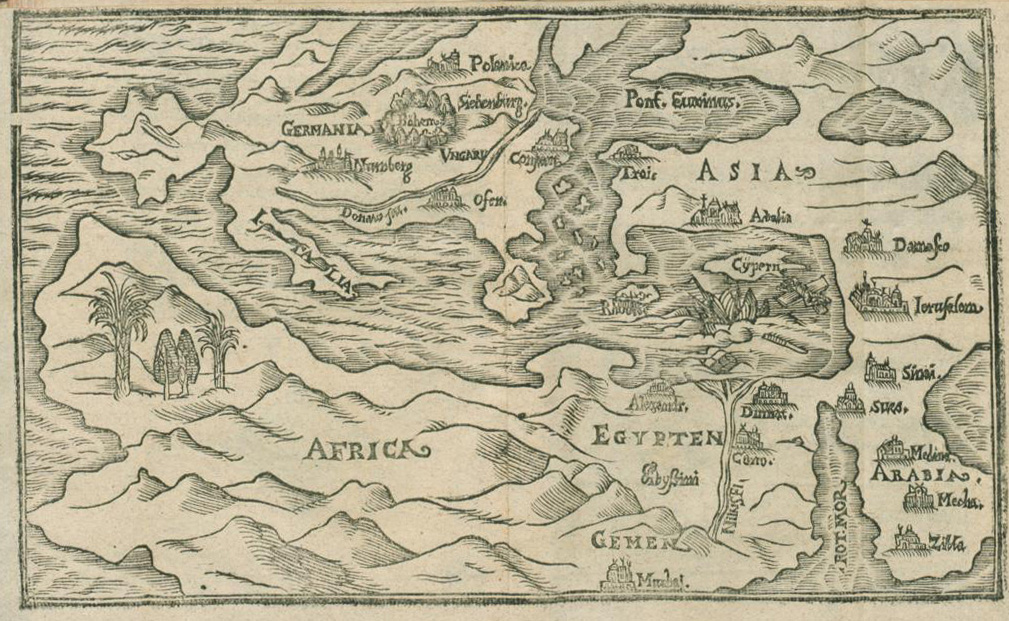

Johann (or Johannes) Wild, a native of Nuremberg, enlisted as a soldier for the war against the Ottoman Empire (“Turkish War”). In late December 1604, he was taken prisoner in Hungary and sold as a prisoner of war to the “Turks.” Wild described his experiences and adventures in the Islamic world and its religion in a travel report, which was printed and enjoyed a certain degree of popularity in the German-speaking world. The book’s introduction portrays Wild as a Christian and a German who describes non-Christian customs and rituals to a German audience based on his own experience. It explicitly equates being German with being Christian. Wild himself uses the attribution “German” in a variety of situations. The book was marketed in such a way as to set “Christian” (i.e., “German”) up in opposition to “Muslim.” At the same time, Wild’s interest in this foreign religion and its practice is quite evident, including, for example, in the inclusion of a Turkish prayer to conclude the book.

Source

[…]

Foreword to Hans Wild’s Travel Book:

To the Good-Hearted Reader

[…]

In this travelogue, the good-hearted reader will find a number of notable things which are not included in other travel accounts, for I know of none other among the Christians or Germans who have been to the places which are famous on account of Mohammed, namely Mecca, where he was born, and Medina Talnabi, where his grave is located. For what one reads in a number of older histories concerning an iron casket in which the false prophet Mohammed supposedly lies—a casket which hangs high up in the vault—is a fable, as the author of the present book himself can attest. Although it makes no difference to Christendom, where or how this false prophet should be buried, but those who cherish the histories might be more than a little interested in a report on the circumstances of the Arabian lands, on the customs and manners of the local population, and how these are a barbaric, bestial, severe, bloodthirsty people in whom there is nothing human except for their outer appearance and in whom any sense of amiability or amity has been completely extinguished and theft, murder, larceny, and other vices are instead considered virtues. Furthermore, what a blind folk these people are, without God or any religion.

How blessed we Germans are in our territories, by the grace of God, especially in those areas where the unfalsified doctrine of the Holy Gospel is ringing out. And also that we are generally blessed with authorities who diligently, to the best of their ability, enforce good laws, order, and discipline, and use these to protect the pious subjects and punish the disobedient appropriately. These authorities thereby not only provide for temporal peace, but also discipline, virtue, and honor, in addition to promoting and maintaining spiritual nourishment, and we can incorporate these into our lives in piety and honor as befits Christians.

And in this we should recognize the inexpressible favor of God and thank God the Almighty from the bottom of our hearts that he has saved us from the heathens’ blindness and darkness and brought us to the wonderful light of the Holy Gospel. Which is thus called a wonderful light because it dazzles [human] reason, just as the owls are blind in the bright light of day. For we, as the apostle says, are not just a people but rather God’s people, who were once without His grace, but are now in His Grace. For this inexpressible grace and favor may the Holy Divine Trinity be praised and thanked. Amen.

Dated, Nuremberg, March 3, 1613 years after Christ’s birth.

Salomon Schweigger: Servant to the Gospel [i.e., preacher] at [the Church of] Our Lady [Frauenkirche].

[…]

The first book is a description of the trip from Nuremberg through Hungary to Constantinople in Turkey, and how he came to be sold for the fifth time. And it has 38 chapters.

Chapter 1:

Hans Wild goes to Hungary to wage war against Bocskai’s forces

When I traveled to Hungary during my years of wandering in 1604 at the age of 19 and found that warfare did not displease me, I signed up for military service on behalf of his imperial majesty against the archenemy and, among the regiment under the flag of the noble Gotthard von Starberg, set out for the fortress Gran [Esztergom]. We were there for over three and a half months (the Turks did not take it that year but the next), for I was then already taken captive by the Hungarians and sold to the Turks in Ofen [Buda], which is where I heard from them how they had captured and seized it. When the Turks retreated from Gran, and we were led with the whole encampment into upper Hungary to Kaschau [Košice] and Eperies [Prešov], Kollonitsch’s regiment was divided amongst the border stations. After our camp had been underway for several days, however, great hunger took hold of us, for we were traveling away from the Danube and the sutlers[1] brought no more wares to the camp. They had all gone back home to Vienna. We poor vassals, however, were starving and miserable: I neither saw nor partook of bread for fourteen days back then, and a great number of the vassals in our party became sick and perished as a result of the cold and hunger. The farmers had all fled from there, and everything in the villages—bread, grain, flour, meat, bacon, salt, lard, cheese, chicken, geese, oxen, cows, and the like—had fled, as well, so that all the chaps were quite impatient and, when they ran across a Hungarian farmer, they harassed him until he was compelled to confess where they had secreted away and hidden everything. Once they knew how the foodstuffs had been hidden in the houses and stables and buried in pits in the fields—grain, flour, bacon, salt, meat, and lard—and the livestock driven into the woods, the chaps all went and dug it up. And then there was great rejoicing!

We also frequently found in the houses in the villages large quantities of pickled gudgeon,[2] goose, chicken, and pork and wine in the wineries. Then the blokes all drank themselves silly and spent a long time in the villages, leaving their quarters ten, twelve, fifteen, or more times to collect more spoils or whatever [they could find]. But many also stayed out [of the villages], for collecting spoils was too risky for them, and they had no nerve for it. It happened not infrequently that Hungarian farmers suddenly ran in without warning while the chaps were roaming about their houses and greeted them with a “Hungarian Earspoon,”[3] so that they sank to the floor and forgot about getting up again.

[…]

Chapter 16

What Happened to the Girl My Master Purchased from the Tatars, How She Ran Away but Was Brought Home Just a Few Days Later

A Turkish merchant lived next to my master’s house, and he had bought the wife of German soldier from Switzerland. She was named Magdalena and came from Switzerland, and she talked the whole day long with my master’s maid through the window, but we never noticed anything sinister about this and paid them no attention. They had, however, made secret plans together to sneak out over the walls and run away, and they actually dared go through with it. They made it over the walls without being seen by anyone, but when they crossed the city walls, they did not know the way and went towards Gran and fell once again into Turkish hands. They had been away five days when they were captured in Fischgrad, which the Turks had already seized, and they were brought back to Ofen [Buda] and [it was] announced in the city: Whoever has lost a captive may give ten ducats to retrieve said captive, and this was shared with us whether it was our captive. So we went there quickly and brought her back to the house and gave the one who brought her ten ducats, just as our neighbor did [for his maid]. And when they were home, we asked why they had run away and our girl confessed that the other had suggested it and convinced her to run away with her, that she knew the way and they had no reason to be afraid, they could escape from this place. The other had also stolen a lot of money from her master, around forty ducats, which they found on her, and for which her master gave her a severe beating and then sold her to someone else. Ours, however, was not beaten, but our master sent her to Gran and sold her there.

[…]

Chapter 37

How the Captive Hans Wild was Taken with Other Boys to the Market and Sold

On the fourth day, the Kapich Wascha came with his servants and led us to the bedestan,[4] where all sorts of valuable things and wares are sold, and there he gave us to a man whom the Turks call Tellial. He took us by the hand and led us around and yelled out [about] us, one after another. Around us the Turks were making their purchases, and it was about three hours until the market finally came to a close, for it is their custom that one keeps selling until everything is gone. One sells everything, and the highest bidder gets the wares. This is the system for everything that is sold: captives, horses, wares, and the like. And when a man wanted to buy me and counted the money, he inspected my hands, arms, body, teeth, head, and the like. This was to see whether they were trying to put one over on him. They do this to everyone, men and women, so that they are not cheated. When, after the inspection, the person pleases them, they pay out the money and take them away. And thus I was sold for around sixty ducats for the fifth time in a year and a half, for I had not been with this Pasha for more than seven months.

[…]

Volume 2: Description of My Journey from Cairo to Mecca

[…]

Chapter 10

How my Master the Persian Left for Mecca with Fellow Pilgrims in the Charaban[5]

When I had served this master for six months, he traveled from Cairo in Egypt to Mecca in the Orient both for business and the pilgrimage. For they go there every year by land and by sea over the Red Sea from Cairo, but first they have to procure the provisions that are not available for the forty days of their journey. Sutlers also go along from Cairo—white Moors who cook along the route and sell the food to others. They have lard, oil, honey, bread, flour, bones, vinegar, garlic, and onions loaded onto camels. The rich Turks, however, take their own such supplies along, so that they have enough for their travels back and forth over three months. There was a suzerain among them who was called Emerhatz in Arabic. He was appointed by the pasha and takes them back and forth to Cairo. The pasha also sends one hundred mamelukes along with them and six guards in case the Moors from the mountains were to ambush them, for example, they would be better able to defend themselves. There are also a number of men on horseback, who are called espahi,[6] or in Arabic, ciutti, who are paid by the pasha. Next in line are around thirty camels, each of which carries two empty baskets where those are laid who become ill during the journey, so that they come along and are not left behind. The Emerhatz goes eight days ahead with his tent; there is a place with a lovely garden and green heath for two miles around the place by the Nile. This garden or place is called Materia in Arabic, and it is said that the Virgin Mary spent seven years here with Christ when they fled from Bethlehem to Egypt. More about this later.

First of all, when all of those have made it to this place who want to be part of the procession, the Emerhatz has his herald proclaim on the evening prior: Those who want to process to Mecca should prepare to depart early tomorrow and come along!

At daybreak, the Emerhatz then announces the departure with trombones, after which, the various parties are placed in the order in which they are to proceed along the entire route so that they do not mingle like livestock. All the camels are bound together, one after another, and each is given water at night and its sacks of waxed leather filled so that it has enough for three days, until we have made our way through the sandy desert to the city on the Red Sea that is called Subeis in Arabic. We rested there for one day and let the camels recover and drink, and each [of us] also replenished our water supply, for one always has to travel for two or three days until one has the next chance to get water. There is nothing more valuable on the whole trip than water, and many die of thirst, as I saw myself. I would often have given a thaler for a drink of water, if I could have gotten any. I frequently saw how the poor people went around the camp and begged. If they were offered bread or food, they put it down again and said, oh my lord, I do not need anything to eat but only, for the sake of God, a spoonful of water.

[…]

Chapter 14

How We Traveled between Two Mountains Where Mohammed Is Said to Have Fought against the Christians.

On the third day, we left Jambo and traveled through an area of mountains and ravines, and there were a number of encounters with the Moors who live in those mountains. They injured many of our party with stones and killed a number of them, and we could not get the upper hand, for they stood high in the mountains and catapulted the large stones down upon us, while we had to proceed along the valley between the mountains. There were also a number of them with tubes [with which] they shot mercilessly at the camels, as with crossbows. And when that had gone on for half an hour, total chaos broke out. Those who could drove forward, for those who were left behind were beaten and everything taken from him, along with his camels and the clothes he was wearing. Around 300 men were left behind in that place and 500 camels, and many were injured only to die two or three days later. My master was also shot with an arrow, but the devil did not want to take him. I would have liked to see it; he was a ruthless dog who left no disgrace unsaid when he opened his mouth. He yelled at me, you Jewish vermin, you Christian vermin, you canine vermin, you swine, you desperate, damned man! That’s how the godless, tyrannical dog slandered me! I often thought about cutting off his head at night and fleeing into the mountains to the Moors, but then, dear Lord, I would have been in a worse situation than before, for, having run from such a tyrant, I would have landed in other hands. I thus commended it to God and asked him to be merciful to me so that I could endure it with patience. And when we had been traveling for two or three days, we came upon a great sandy heath, where the sand was as fine as flour. There the Turks and Moors began to yell, "Oh, God, protect us so that no great wind kicks up, O help us, God!" When we had gone one three or four hours through this area, we came to two mountains, between which we had to pass. One was made of fine, clear sand, the other of large black stones, though there was no other stone to be found far and wide. The Turks ran to the sandy mountain and took sand in both hands, rubbing their faces with it and saying: Oh, you blessed Mohammed, and so on. I asked a Moor with whom I was well acquainted what the meaning of this was, and he told me that it was here that the Turks battled the Christians, but the Turks felled all the Christians. And he said that Mohammed had stood on the sandy mountain with his followers and the Christians on the other mountain of black stones. And the Christians threw stones over [at the Turks], which turned into pure sand, and the Turks threw sand, which turned into stones. To which I replied, that is a pack of lies, and if I had seen it myself, perhaps I would believe it then. At this, the rogue got quite upset with me and said: By God, you are a Christian dog. Be quiet or I’ll hit you. I had said a very terrible thing, [and] he refused to say a word to me for a long time, and I was glad that I escaped [worse retribution] thus.

Chapter 15

How We Traveled through a Sandy Desert and the Masses Fell to Their Knees and Called Out to God and Their Mohammed to Show Mercy upon Them, Because It was There Where Mohammed Is Said to Have Heard the Angels in Heaven Singing.

A few days later we came upon a sandy desert which it takes two days to traverse. There is a mountain there, and before they traveled across it, they stuffed the camels’ bells so that they did not ring until they had crossed the mountain. (For when the Turks or Moors travel, they hang large bells on their horses and camels so that they can be heard from a distance.) And so they traveled over the mountain silently, and most of the Turks and Moors went ahead of the camels and made an Abdest with the sand. Abdest is a sort of cleansing, the hands and face, and also the feet, and after that they prayed twice to God and their Mohammed. The others looked to the sky and said, this is where our Prophet Mohammed heard the angels singing in heaven and they asked one another constantly, hey, do you hear something? I could not resist and asked them, Oh, you poor people, do you really believe such things? And I laughed. They called me a Christian dog and fussed at me very much, but I did not ask much about it but laughed at their blind faith.

[…]

Volume 4: The Fourth Book is a Description of the Journey out of Egypt through Turkey to Constantinople and Then to Poland and Back to Germany.

Chapter 8: Hans Wild Travels from Poland to Germany

We were stopped in Iași for three days, for everyone had to pay tolls on the goods they were carrying. This city is not large. It looks like a market village, [for it] has no walls around it and a run-down palace in which the prince holds court. The residents are Vlachs, Russians, and Poles, and are a tyrannical people, and are not at all safe from the Tatars. The poor peasants are constantly fleeing from the villages and hiding in the large forests.

From Iași, we traveled eight days to Camenitz, which is the first border station in Polish territory. This city is tremendously fortified but not large. It also has a fortified palace in which several hundred hajduks[7] reside. In this city, my master’s coachman ran away, having stolen a horse and tin [of money].

From Camenitz it took us eight days to reach Russian Lemberg, where the merchants unload their goods, and I remained with my master until the yearly market in Jarosław was over.

In Jarosław, I met a German merchant named Lorentz Stauber, a wealthy, well-mannered man who traded in velvet and silk and lived in Kraków, the royal residence city.

On August 30, I traveled from Jaroslaw to Krakow; my master gave me a thaler and discharged me honorably for my good behavior.

When I arrived in Krakow, Lorentz Stauber loaned me 12 guilders for provisions, which I repaid to his father-in-law Erasmus Schilling in Nuremberg on October 22.

The said Lorenz Stauber in Krakow showed himself to be most honorable and amiable towards me, for he had heard that I was from Nuremberg and had suffered and endured a great deal in Turkey.

After that I traveled from Krakow to Prague with two coachmen who were taking Jews there. There I took a break for four days before setting out for Nuremberg.

Now I have sufficiently described my journey, and I thank God the Father for his mercy and his dear Son Jesus Christ, my Savior and Helper in need, who so graciously protected and shielded me on all my paths over water and land and brought me in the end back to my dear fatherland. His be the praise, honor, glory, and thanksgiving, now and for all eternity. Amen.

Notes

Source: Johannes Wild, Neue Reysbeschreibung eines Gefangenen Christen: Wie derselbe neben anderer Gefährligkeit zum sibendem Mal verkaufft worden/ welche sich Anno 1604. angefangen/ und 1611. ihr end genommen/ Darinnen außführlich zu finden/ die Stätt/ Länder und Königreiche/ sampt deroselben Völcker/ Sitten und Gebräuch/... Insbesonderheit von der... Walfahrt von Alcairo nach Mecha/... Item von der Statt Jerusalem/... von der Statt Constantinopel... In IIII. unterschiedlichen Büchern begriffen / Auffs fleisigst eigner Person beschreiben und außgestanden Durch Johann Wilden/ Burgern inn Nürnberg. Mit einer Vorrede Herrn Salomon Schweiggers S. Predigers zu unser Frauen daselbsten. Nuremberg: Locher, 1623, title page, excerpts from the unpaginated foreword by Salomon Schweigger, pp. 1–2, 17–18, 43, 56–57, 61–63, 254–55. Available online at: https://digitale.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/vd17/content/titleinfo/96192